The Internet’s Own Boy: Activating the Internet Activists

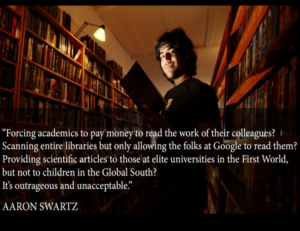

In January of 2013 it made news around the world that prominent US internet freedom activist and programmer Aaron Swartz had committed suicide. At the time of his death- and reportedly responsible for it- 14 federal hacking charges had been brought against Swartz. These charges would have resulted in 35 years prison time amongst other punishments as a result of Swartz downloading millions of academic papers from online archive JSTOR. Believed to have been motivated by principles laid out in his Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto Swartz intended to make knowledge free for all rather to only those who could afford to pay for it. The internet itself was seen to weep in unison as tributes flooded online social media platforms. Included in these tributes were prominent figures with the inventor of the World Wide Web himself, Tim Berners-Lee, tweeting “Aaron dead. World wanderers, we have lost a wise elder. Hackers for right, we are one down. Parents all, we have lost a child. Let us weep.”. Brian Knappenberger, the owner of Luminant Media which “finds the stories behind the headlines” sensed an opportunity to create something from this tragedy and following the theme of Berner-Lee’s tweet, the movie The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz (Brian Knappenberger, USA, 2014) was created.

Knappenberger started this endeavour by crowdfunding the movie on the global crowd-funding platform Kickstarter. This served multiple functions for the movie. Not only did it allow an independent film to be created but the filmmaker was also able to tap into a ready-made audience- the community who were already interested in the life and death of Aaron Swartz. Through the bringing together of this community and having all 1,531 backers work together to surpass the $75,000 goal the takeaway message of the movie that people can be brought together online and take real action to achieve their goals was actualised- albeit on a much simpler scale.

Participant Media (PM)– a production company known for supporting films that advocate social and political change partnered up with the film production. This meant that the film would reach PM audiences already interested in social and political activism. PM provided support for the film to achieve more than holding screenings as it supports activist groups and holds a significant political outreach which would help with lobbying congress for change- which they did. Importantly PM also accepted the creative commons licence of the film which aimed to make the movie free for everyone to view– in keeping with much of Swartz’s work to provide knowledge to all. On the same day of the film reaching theatres it was also released digitally through a creative commons Attribution-NonCommerical-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence in recognition of the time and effort Aaron had spent on creative commons and also raising awareness of it. Knappenberger pledged to spend any profit the movie made on causes Aaron cared about further proving the movie was not made for a commercial profit but to bring information to public attention.

One of the most important pieces of information brought to public attention is that the CFAA enacted in 1984 and responsible for 11 of the 14 charges brought against Swartz is outdated and is too easily used against targeted individuals– Swartz being a case study of this. This is due to the subjective nature of terms and agreements rules- an example of “be nice” is given which if broken means you have committed a crime. Knappenberger expressed that he made the movie with three goals in mind. He hoped to: expose the criminal and justice system as broken, raise awareness of how “ridiculous” and outdated some laws are- such as CFAA, and lastly he hoped to convey how the internet had the ability to be used for: social justice causes, grass roots organising, and putting skills in the service of public good. As a film documenting a social injustice- the overly harsh penalising of Swartz as a warning to other hacktivists- it relies heavily on testimony and creates what Rorty refers to as “rights claims”.[1] These rights are defined by Rorty as “claims for recognition and redress on the basis of one’s humanity”. The film opens and closes with family footage of Swartz as a child which could be considered an attempt at humanising him by showing a private and personal insight into his past. The purpose in humanising Swartz functions to both create a sense of empathy for this little boy who met a tragic fate and to create a degree of relatability for viewers. This was an ordinary US citizen, someone’s child and brother. This sends the message that what happened to Swartz applies to everyone who uses the internet. This message is confirmed through the narrator directly addressing the audience and telling them that by not reading terms of use agreements viewers could be committing a felony. The films also use of expert testimony from the legal director of the electronic frontier foundation who states that it is “crazy” for the legal system to have any say in the website use of service violations which include subjective instructions which are difficult to define and a crime to disobey.

Overall the films function of raising awareness and beginning a conversation on the issues it covers has benefitted from its creative commons licence. Through being available to view it for free an opportunity was provided for hosting websites to link to news and petitions of related causes. Aaron’s Law which aimed to reform the CFAA to prevent such severe penalties for such minor abuses of terms and conditions was successfully pushed back before US congress even gaining the backing of a presidential candidate. Unfortunately, once again Aarons Law died in congress, but this could be viewed as indicative of a much larger issue within congress itself. The Internet’s Own Boy can be considered a success in fulfilling its goals of motivating a collection of people to push for a change outlined by the film. It’s methods of reaching its target audience of those willing to create change and interested in internet laws was effectively navigated through the production, distribution, and awareness-raising of the film by considering who the target audience is and how best to reach and motivate them into action. Although the film did not achieve its main goal with Aaron’s Law it is still available online for all to view and utilise freely and it continues to contribute to a much wider discourse on usages and rights on the internet.

[1] Sam Gregory, “Transnational Storytelling: Human Rights, WITNESS, and Video Advocacy”, in American Anthropologist Vol. 108, No. 1 (2006) 193.

Image source: https://www.facebook.com/pg/theinternetsownboy/photos/?ref=page_internal