‘KNOW THE SIGNS’: How effective is ‘Evan’ in the prevention of gun violence?

Following the Sandy Hook school shooting in December 2012, the ‘Sandy Hook Promise’ charity was established within America to support victims of gun violence and promote methods of prevention. Four years later 2016 saw the release of the charity’s PSA video ‘Evan’, which went viral obtaining over 5 million views in four days. The piece also received recognition through numerous creative awards, 10 of these accredited at the 2017 Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity.

Produced by New York advertising front-runners BBDO the two-minute video entices audiences through its depiction of high-school love; implied through the exploitation of romantic genre codes. However, in a chilling turn of events the clip’s half-way point is marked by the outbreak of a shooting. Emphasising the inconspicuous nature of gun violence ‘warning signs’, the video’s opening is replayed to reveal the future perpetrator in the background exhibiting signs of planning an attack.

Reception of ‘Evan’

Whilst the video addresses a prevalent issue within American culture, I believe the rapid accumulation of views is a result of its innovative twist; which places the spectator in the position of a perpetrator’s associates failing to identify early signs. The spectacle of ‘shock’ established within the video responds to contemporary society’s ‘click-bait’ trend; alluring viewers to watch by challenging them not to be ‘duped’( exemplified within articles by tabloids such as USA TODAY).

Analysis of social media confirms the success of exploiting such trends, should Sandy Hook Promise’s motive have been to raise awareness through exposure. A number of personal responses to the video’s shocking twist can be observed via YouTube where vloggers have uploaded ‘reaction videos’, filming themselves watching the campaign and capturing their initial responses. Such videos contribute to the spectacle of ‘Evan’, aiding its popularisation as the vloggers’ subscribers are consequently indirectly exposed to the PSA and its politics surrounding gun violence.

Manipulation of the spectator and rhetoric of ‘pranking’

To misguide the spectator, the PSA intentionally embodies conventional romantic tropes such as an uplifting acoustic musical score and a mysterious love-interest to distract from the images of bullying, gun-handling tutorials and antisocial behaviour occurring in the background. The lack of focalisation upon violence-related visual signifiers in the opening ensures the shocking reveal of the attack, intended to emulate real-life confrontations and emphasise the message that anyone can be involved in such disasters.

Through its manipulation of the viewer, the PSA could be interpreted as feeding directly into Christine Harold’s ‘pranking’ discourse permeating media activism. Harold suggests that through ‘pranking’ activists are able to ‘raise awareness’ through non-conventional means. This is applicable to ‘Evan’, which masks its political agenda under the guise of click-bait, only to later reveal its role in publicising the ‘Know the Signs’ campaign. This method of pranking is particularly effective for S.H.P as the prank itself attracted mass amounts of media attention, providing platforms to promote the charity’s campaign.

Life after ‘Evan’

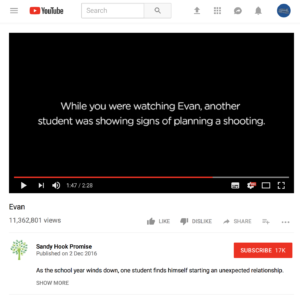

The exposition of the PSA’s central theme is followed by two intertitles directly addressing the spectator: ‘whilst you were watching Evan, another student was showing signs of planning a school shooting. But no-one noticed’. Subsequently, the opening minute of the clip is replayed with a remodelled darker aesthetic to expose the scenes’ underlying horrors. Casting a shadow over the previously foregrounded protagonist Evan, the blonde student in the background of the mise-en-scène is illuminated to draw attention to his performance of ‘warning signs’.

Additionally, the vocals of the originally upbeat ‘feel-good’ musical score are isolated within the replay, slowed-down and imbued with echo effects to correspond with the clip’s new-found horror genre. The seamless diffusion of romance into horror consequently parallels the sudden and devastating impact of gun violence upon a person’s life.

Through the use of direct address, the video deconstructs the fourth wall between the viewer and the film with the intention of evoking a sense of guilt through a perceived failure of

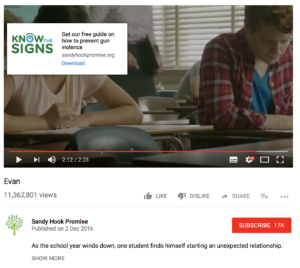

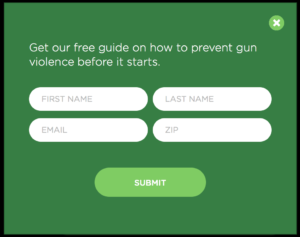

acknowledging ‘the signs’. In the subsequent seconds the original YouTube video uploaded by Sandy Hook Promise is overlaid with a ‘pop-up’ advertisement, directing the viewer to their website[9];more specifically to a ‘know the signs’ ‘free guide on how to prevent gun violence’.

Reaction and Propagation

Exploiting the advertising tools embedded within YouTube, Sandy Hook Promise is able to establish a bridge between their PSA and website, which specifically highlights the reactionary response they desire their viewers to embody. Notably, to obtain a copy of the ‘Know the Signs’ guide, an individual must enter a full name, email and zip-code, suggesting a discrete mailing list sign-up which will aid the maximised propagation of the charity’s future campaigns.

Resultantly, the campaign is also in alignment with ‘governmentality’, a term coined by Michel Foucault to articulate the process in which techniques and procedures direct human behaviour. As aforementioned, the PSA critiques society’s current ignorance towards ‘early signs’, through suggestions that people are unaware of what to look for. At the end of the clip intertitles expand upon this idea further: ‘gun violence is preventable when you know the signs. Learn them now at sandyhookpromise.org’.

Employing the imperative ‘learn’ in a direct address to the spectator, the video outlines a reactionary practise which will theoretically benefit the dominant ideology of eradicating gun violence. Providing links to a ‘how-to’ guide, the PSA additionally provides its spectator with the agency and resources necessary for self-improvement.

Is ’Evan’ effective?

Whilst the campaign directs its spectator towards a multitude of educational resources, the effectiveness of ‘Evan’ in contributing to gun violence prevention is questionable. Despite its pictorial guide aiding the recognition of ‘warning signs’ the campaign fails to provide evidence of how such recognitions will actively prevent future attacks. The campaign also disregards the elusive nature of the ‘signs’ highlighted. Despite evidence of future-perpetrators often displaying anti-social behaviour, a wrongful accusation of a child could further isolate marginalised individuals and consequently catalyse dangerous outbursts. Speaking cynically, the lack of progression in the prohibition of possessing firearms in America further problematises the work of Sandy Hook Promise. How effective can an anti-gun-violence PSA be within a society that possesses such liberal laws in relation to the possession of firearms? Consequently, I believe that ‘Evan’s success lies in its ability to raise awareness. Appearing on accessible platforms such as Facebook and YouTube and exploiting contemporary trends such as ‘click-bait’ the PSA encourages circulation of topical discourse. Whilst this alone cannot prevent the tragedy of gun violence, persistent discussion of such ideas can exert pressure on higher powers to instigate change.