Controversy Behind the Dove Soap Ad – Exploring Identity Complexes of Media Reception

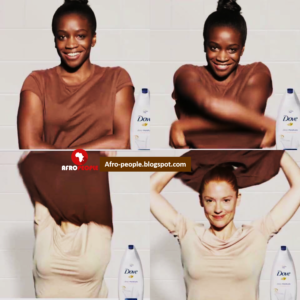

The message behind this ad is intended to be clear. From an aesthetic perspective, the ad uses formal elements to show three different women of different racial backgrounds. They are all wearing plain t-shirts that match the color of their skin tones. The background is pure white, putting all attention on these women. Furthermore, the message of the ad matches the simplicity of the aesthetic. It is using the images of one woman taking off her shirt to reveal another woman of a different racial background to suggest that women of all skin colors use Dove soap. The underlying message that the ad is trying to get across is that Dove as a company embraces diversity.

However, through looking at the media response it received it becomes clear that public opinion did not absorb the message the company intended. Through various social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram the ad has been cut and shared to portray an opposing message. Through snipping the video, the ad showed the black woman taking off her shirt to become the white woman, all while omitting the third woman entirely. The snipped ad suggests that the black woman becomes the white woman after using Dove soap. This furthers the idea that whiter skin is the desired beauty standard. Because of the poor attention played to the formal elements, where one can easily snip a video to get the opposite message across, the ad was deemed racist and started a movement. Under the hashtag “#donewithdove”, many people took to social media to express their outrage and called for a boycott of Dove products. Furthermore, the edited ad has been turned into various memes, all poking fun and drawing more attention to the fact that Dove soap promotes whiter skin as the desired beauty standard.

When looking at the movement as a whole, it becomes clear that it is a reflection of the identities and attitudes of those who initiated it.

Ella Shohat and Robert Stam explore the idea of unthinking Eurocentrism, particularly while looking at the paradigms of looking. One of the dominant esthetics that came out of colonialist discourse was that of the Eurocentric gaze, where film and TV overwhelmingly furthered the idea that legitimate beauty came solely from white women. This form of hegemony made women of color feel exiled from their own bodies for not being considered the standard of beauty. Shohat and Stam shed light not only on the once dominant racist hegemony but also the intricacies of the process that women of color went through to accept and embrace their bodies as beautiful.[1] Although the authors delve into how women of color eventually learned to embrace diversity, Shohat and Stam fall short of exploring the complexities of accepting support for diversity.

Embracing diversity can be a difficult transition depending on who is promoting it. The company Dove has not always been active in promoting this message of diversity. The brand had been under scrutiny in the past from other ads as well as the messages on their products for promoting white as cleaner, more beautiful skin. It could be assumed that the company put out this clear message of promoting diversity to counter these assumptions. Regardless of the company’s intentions with the ad, it became clear that many would much rather manipulate the ad to further its preconceptions of the company rather than accept Dove as an all-inclusive company. Even though Dove wanted to disassociate itself with the idea that its products further racist beauty standards, the reception to this ad shows how the transition from the Eurocentric gaze to that of an all inclusive one is not straight forward and all forgiving. A company cannot simply disassociate itself with promoting a Eurocentric gaze simply through making an ad that directs that message. The process has much to do with the identity of those promoting it, with more attention put on past reputations and actions than the desire to move beyond.

Although Saidiya Hartman explores the faults of testimony, her perspectives can be translated to this particular ad and the media controversy surrounding it. In her book, Hartman finds faults with the white abolitionists’ testimonies of black slavery. Specifically, she questions why these testimonies must put white bodies in the perspectives of black bodies to consider the suffering as legitimate.[2] Similarly, the original as well as the cut ad shows how the black woman taking off her shirt first has to become the white woman. Like how Saidiya Hartman found fault with abolitionist testimony, many black women find fault with the order of the women, specifically at the fact that the black woman had to first turn into the white woman to show how black skin can look just as beautiful as white skin. This point is furthered even more through the cutting and sharing of the video, all done to gain more attention towards Dove’s racist products. What would be a true expression of celebrating diversity would be an ad not including a white woman. That way, it would further the message that all women of color can be seen as beautiful on their own, rather than constantly having to be related back to white women to do so.

This movement as a whole is an example of what Patricia Zimmerman calls media piracy, where parts of a whole product are cut to produce new ideas for circulation.[3] The social media platform under which the movement was shared shows that media piracy is for the masses, where anyone with a computer can commit media piracy. This shows that media piracy today can reflect the dominant ideas of the masses. Through tying the points of Shohat and Stam as well as Hartman, one can understand how intentions form for media pirates. This ad shows how good intentions don’t guarantee positive responses. Dove tried promoting a simple message, but it was ill prepared to face the identity complexes that tie into media reception.

Link to Ad: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zkIrbVycAeM

Link to Meme: https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1302637-dove-facebook-ad-controversy

[1] Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media (London, 1994), p.322-324.

[2] Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p.19.

[3] Patricia Rodden Zimmerman, States of Emergency: Documentaries, Wars, Democracies (Minneapolis: University Press of Minnesota, 2000), p.155.