CLIP: Adam Price’s ‘Borgen’ and the Danger of Framing Optimism as Activism

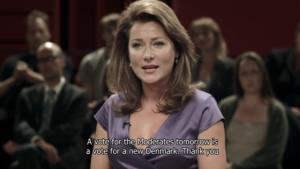

Adam Price’s Danish television drama, Borgen, explores the shock election of Denmark’s first female Prime Minister, Birgette Nyborg, a minor yet idealistic centrist politician. The following clip of Borgen takes place during the closing speeches of all main party candidates as Nyborg improvises and addresses her audience directly.

In this sequence, Birgette directs a series of accusations against her fellow politicans: “I believe it’s a myth that we’re all equal […] it’s a waste of time to discuss how to avoid it.” Price presents his protagonist as an underdog heroine figure, who faces off against the larger parties in the presence of mass media. Notably, when interviewed by The Guardian, Price aligns Denmark’s political climate with the forward-thinking outlook which Nyborg embodies: he claims his country is the “model of state labour” with its system built on the “principles of flexibility, security and equality.” He thus positions his show as a form of optimistic ‘political work’ or ‘activism’ which practices socially productive ideals, like his nation, as a model for governing.

However, this optimistic outlook is constructed as a convincing illusion. This can be examined in reference to Jean-Luc Comolli and Paul Narboni’s article Cinema/Ideology/Criticism in Screen.[1] They assert that cinema is a product of the dominant Capitalist ideology and provide a useful, albeit rigid, tool of categorisation to explore this. For instance, ‘Type A’ cinema is defined as ‘unconscious instruments of the ideology’, which repackage social needs as discourse. Here, public taste is created by the dominant ideology, not independently, as an endless cycle of consumption.[2]

Significantly, the progression of events in this clip of Borgen parallels this theory. Price recycles the same rhetoric you’d come to expect: Nyborg diverts from her speech, she dramatically shuns her pre-written papers and eventually her ‘unexpected’ outburst was met with assuring positivity. The desire for advocacy is diluted as the viewer is offered an affirming applause in response to the protagonist’s ‘relatable’ declaration. This cathartic release is satisfying, which perpetuates the illusion that activism is no longer necessary. In effect, this re-affirms Comolli and Narboni’s argument as the politics of the dominant figures, which Nyborg appears to be against, are actually re-enforced.

Moreover, this strategy ensures that true levels of inequality are ignored. For instance, echoing Price’s assertions, many American liberals like Bernie Sanders have praised Denmark’s welfare state. However, few realise how backward their immigration policies are.

In 2005, Denmark’s government introduced legislation requiring U.N. resettlement refugees, mostly Muslim, to be assessed for their “integration potential”, and from 2007-2013 Muslim refugees were no longer in Denmark’s target groups for resettlement. Furthermore, Mrutyuanjai Mishra in Mind the Gap claims racism is “mainstream” in Denmark. She comments on the rarely reported ‘Ghettos’, where a large concentration of immigrants, the poor and jobless reside. In addition, Machala Clante Bendixen, head of Refugee Welcome in Denmark found in 2015 that only 29% of Iraqis immigrants were accepted into the country, along with 35% of Afghans. This fell short of Sweden, Norway and Germany. It seems that the Danish government has spent the past decade implementing some of the most restrictive immigrant policies in Europe.

From what we can see, consciously or not, Price utilises Borgen not to tackle this inequality, but to deflect from it. From just glancing at the clip, there is a visible lack of diversity on screen, which is instead occupied by a sea of white faces. Notably, as a programme that frames itself as politically progressive, Borgen’s incapability of practicing the politics it preaches on camera is more than questionable. Moreover, Birgette’s speech is obtrusively vague and doesn’t begin to address the levels of prejudice facing her country. The rejection of the “free market” and the “widening” gap between the rich and poor are just empty words; the scene falls problematically short of acknowledging any specifics.

This can be further developed in reference to Tomas Gutierrez Alea’s work, The Viewer’s Dialectic, which provides a critical outlook on Capitalist cinema as a “major vehicle to encourage viewers false illusions and serve them as refuge.”[3] Arguably, Borgen represents this “vehicle” which provides a substitute reality in which the spectators are kept from hard truths. To expand, Jasper Rees comments that part of the appeal of the show is that it gives politicians “the benefit of doubt.” It could be argued that Price’s constructed reality offers an optimistic outlook on the social politics of his Danish politicians to allow his audience a satisfying sense of “refuge”, or even accomplishment, upon viewing it. The drama pushes the viewer to buy into the concept that ‘things aren’t as bad as they appear.’

Furthermore, this idea of ‘reality’ as ‘illusion’, can be further explored through Comolli and Narboni’s article. Borgen can also fit into ‘type D’ of their categories: cinema that has a subversive political agenda, but is unsuccessful due to its realistic aesthetic. Here, the realist aesthetic does not reproduce “the way things are”; it is in fact a reproduction of the dominant way of seeing.[4] In the sequence, Price sets up his own platform to make a political ‘protest’ in an effort to render it as close as possible to its contextual reality. The parties all have their counterparts: The Moderates (De Moderate) is based on the Danish Social Liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) and and The Labour Party (Arbejderpartiet) on the Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterne.) Even the broadcaster, TV1, has its own real-life twin, DM1.

Ironically, although Birgette claims she wants to establish a “new way of doing politics”, Borgen is settled so deep within its political context that it assimilates itself with the staggering inequalities which it claims to reject. This has led to assumptions in the U.S. that watching the show can be a substitute for learning Danish politics. For example, Emily Tamkin, for foriegnpolicy.com, claims Borgen can teach us that “Danish voters rewards decency” and do not reward “craven politicians.”

Therefore, we can see how the programme’s attempts to replicate reality has perpetuated the false dominant ideology of a ‘progressive’ Denmark. This re-affirms Price’s drama as an optimistic look at how the Danish political climate could be, but not a controversially revealing one about how it really is. Consequently, Borgen can only offer itself as a form of consolidation for a burdened spectator.

Here, the danger of Borgen is how it optimistically presents itself as doing ‘political work’, but when taken apart, is just a well-constructed drama with little value of advocacy. In effect, it disregards true inequality in favour of a comforting illusion for its viewers. This makes the ‘activism’ that Price promotes nothing but counter-productive or even worse, deceptive.

[1] Jean-Luc Comolli and Paul Narboni, “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism,” Screen 12, no. 1 (1971): 27-38.

[2] Comolli, Narboni, “Cinema”, 32.

[3] Tomas Gutierrez Alea, “The Viewer’s Dialectic”, trans. Julia Lesage, Jump Cut, no. 29 (Feb 1984): 18-21.

[4] Comolli, Narboni, “Cinema”, 30.